Much has been written on the power of storytelling, as a tool for motivating people and advancing causes. Stories are the basic way humans share information and influence people. We here at Resource Media have been following one particular story since the New Year.

The standoff between anti-government militants and federal authorities at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge has captured attention nationwide. But this story is more than an unfolding news drama. It is also a competition between two narratives, each advancing a particular vision for the future of public lands in the American West.

The saga presents a powerful opportunity to examine how information is shaped into the familiar molds of competing stories. Resource Media took a close look at the fundamental elements of any story — conflict; characters; setting; symbolism and imagery; and audience – and how they were presented and perceived by various parties.

Element 1: Conflict

Every story pivots on a core conflict. In the political news, it’s “Candidate A vs. Candidate B.” On the sports pages, it’s “Home Team vs. Visiting Team.”

Ammon and Ryan Bundy started this story by taking over the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. “We’ve taken over their fort,” said militiaman LaVoy Finicum, “and it won’t go back to the federal government.”

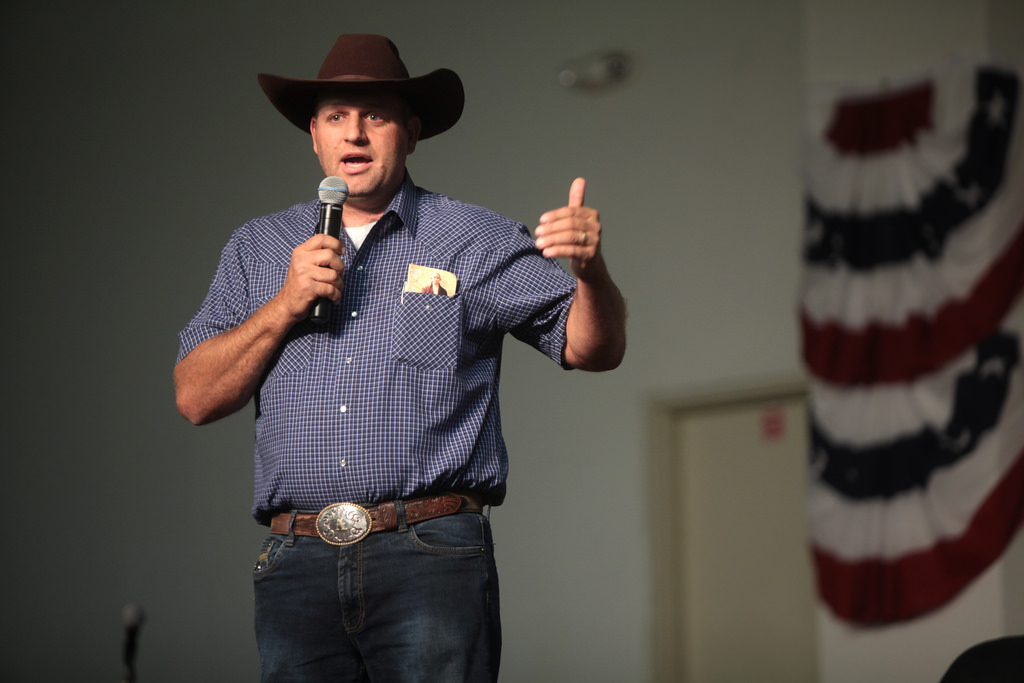

The Bundys tried to frame the standoff as “salt-of-the-earth ranchers v. tyrannical government.” They leveraged a controversial Oregon rancher’s legal battle to vilify the federal government, writ large. Freedom was their primary core value, wrapped in the secondary value of patriotism.

The Bundys tried to frame the standoff as “salt-of-the-earth ranchers v. tyrannical government.” They leveraged a controversial Oregon rancher’s legal battle to vilify the federal government, writ large. Freedom was their primary core value, wrapped in the secondary value of patriotism.

But Bundy’s critics, led by local residents, conservationists and sportsmen soon reframed the narrative as “dangerous extremists v. democratic principles.” With plenty of help from the militants’ own missteps, they turned the focus to core values of fairness, democratic due process, community and respect for nature. This new frame more accurately painted the militants as enemies of freedom, not its defenders.

Element 2: Setting

Harney County is more than a lonely, seldom-visited corner of Oregon. It is classic western high desert: cowboy country, with real cows and cattlemen, riding the purple sage. It is a little slice of the American West, drenched in the cowboy myth that is recognized around the world. This story had a setting straight from a John Wayne movie.

Element 3: Characters

Stories tend to have three kinds of characters: heroes, victims and villains.

The Bundy Bunch tried to paint themselves as heroes — patriots, pitted against villains represented by the federal bureaucrats and agents. They painted the victims as rural residents, whose way of life they said is being trampled by the villains. They urged local community members to take their side, but were disappointed.

In the larger narrative, the Bundy Bunch themselves became the villains. Heroes were local law enforcement, particularly the Sheriff, local ranchers and members of the Paiute tribe, who forcefully denounced the Bundys. Representatives of the federal government wisely kept a low profile. A heavy-handed display of federal power would have played into the Bundy narrative.

Element 4: Symbolism and Imagery

The Bundys exploited powerful iconography. They dressed in western togs; they posed a horseman waving an American flag before the news media every morning; Ironically, these powerful images also worked against them as their actions made them look more and more like bullies and hypocrites. Also, their flagrant display of firearms, particularly large-capacity assault rifles, probably frightened more people than anything else. The guns the Bundys saw as symbols of freedom, others saw as a dangerous menace.

In blogs and other stories, conservationists and others pushed out more of the traditional, iconic images of the refuge at its best, images of sweeping vistas and abundant wildlife

Element 5: The Audience

At the end of the day, all stories are interpreted through the world-views of the audience. Clearly, the Bundy protests and other anti-government actions actions appeal to some people. Others scoff. Others are afraid or angered.

The reaction to the FBI’s release of the aerial video footage of the shooting of LaVoy Fincum is a classic example. Some watched the footage and interpreted it as clear evidence that police were justified in killing Finicum. Others saw the same video as proof Finicum had been assassinated. As always, the “truth” was in the eye of the beholder and “facts” are filtered through individual beliefs and prejudices.

Bottom line: In a chaotic world overloaded with information, stories are one primary way we make sense of it all and try to impart meaning. Savvy strategic communicators understand all elements of their story, competing narratives and how their audience perceives and responds to them.

— Ben Long